It must be a nightmare for any investor to realize they were operating in the dark. When the only financial visibility comes from opaque MIS decks crafted by founders, it becomes nearly impossible to distinguish a thriving business from a well disguised crisis.

The BluSmart Mobility debacle is a painful reminder of this exact problem, and it could happen again. If the Indian venture ecosystem does not evolve from reactive scrutiny to proactive oversight, this won't be the last time investors find themselves blindsided.

The BluSmart Collapse: A Cautionary Tale

In April 2025, BluSmart, India’s most high profile electric ride hailing startup, abruptly halted operations. Investors and the public were stunned when SEBI disclosed that co-founders Anmol and Puneet Singh Jaggi had allegedly misappropriated ₹978 crore in loans meant for EV acquisitions.

Instead of purchasing 6,400 vehicles as promised, the company only acquired 4,704. The rest of the funds were traced to luxury real estate, premium golf equipment, and personal indulgences. One of the most glaring discoveries: a ₹43 crore apartment in Gurugram’s exclusive DLF Camellias registered under personal ownership.

Worse still, BluSmart had falsified documents, including conduct letters from lenders, to mask defaults. Investigations revealed that government entities like Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL) were also misled, with PSU funds being rerouted through affiliated firms.

All of this unfolded under the noses of institutional investors, many of whom only realized the severity of the issue after operations were suspended and audits were ordered.

Investors Were Left Blind

This isn’t just a case of fraud, it’s a case of absence. Investors had no direct view into the accounting backend. They relied on quarterly presentations or investor updates prepared by the same executives misusing the funds.

There were no automated checks, no reconciliations beyond what the founders presented, and no system in place for investors to independently verify cash flow versus claimed metrics. It wasn’t until SEBI stepped in that the tangled web unraveled.

What the Books Would Have Shown

Let’s explore what internal accounting data could have flagged, had investors been looking in the right place:

- Disbursement vs Utilization of Capital: Investors could have matched the sanctioned loans for EV procurement with the fixed asset register in real time. The shortfall of nearly 1,700 vehicles would have emerged instantly.

- Related Party Transactions: Regular and unusually large payments to Gensol Engineering, the affiliate company, could have raised alarms. Especially if these were not matched with incoming invoices or service justifications.

- Operating Cash Flow Trends: BluSmart reported fleet expansions and revenue growth, yet was defaulting on basic loan payments. The negative cash flow trend, masked by fresh disbursements, would have shown up if operating vs investing cash flow was broken out cleanly.

- Bank Charges and Loan Defaults: Hidden in transactional data, EMI bounce charges, late fee penalties, and bank notices often surface first before defaults are officially announced. These would’ve shown up as outlier charges.

- Mismatch Between Revenue Metrics and Payouts: If the claimed ride volume was up, but fleet maintenance costs and driver payments were erratic, that discrepancy would have signaled inflated top line figures.

- Fake Conduct Letters: These might have been harder to catch in the books directly, but a missing lender confirmation workflow, where actual bank statements are reconciled against declarations, could have prevented the reliance on forged letters.

Bridging the Oversight Gap

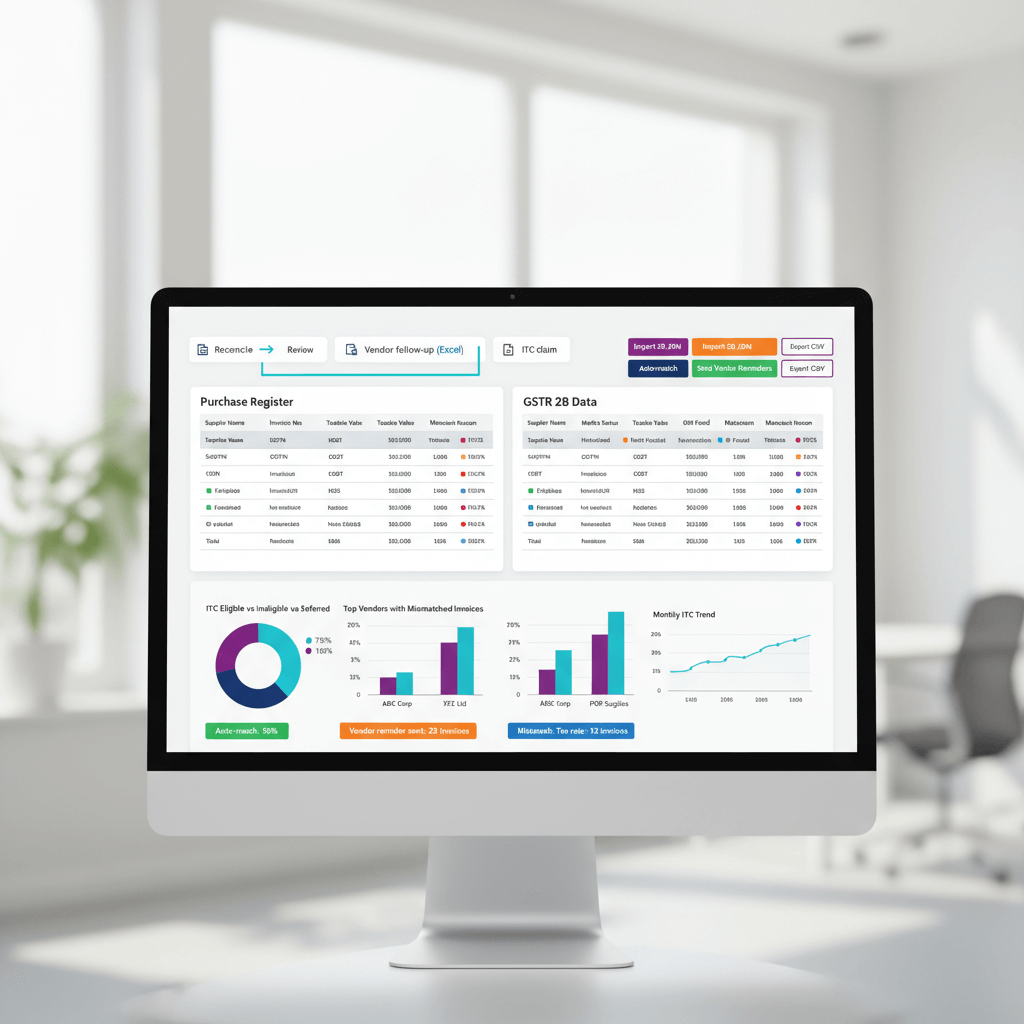

The lesson here is not just about catching fraud after the fact. It’s about structuring investor access in a way that real time oversight becomes standard, not optional. Here are a few examples of what should have been available to institutional investors with system level access to accounting data:

- Live cash reconciliation dashboards to verify runway, burn, and real liquidity

- Flagging of any related party transaction above a preset monetary threshold

- Asset registry crosschecks with loan drawdowns for immediate alerting

- Alerts on any loan or EMI payment issues, especially recurring charges

- Deviation reports between claimed metrics (MIS) and system entries (books)

- Trend breakdowns across revenue, expenses, and capex allocation by category

These insights aren’t futuristic. They are very much possible with current tools, if only investors demand access to them.

The Future of Financial Oversight

India’s venture ecosystem is growing. So are the stakes. The BluSmart episode should be the final wake up call. Relying solely on MIS decks, founder updates, and quarterly board meetings is no longer enough.

The technology exists. The question is: will investors use it before the next BluSmart happens?

Sources

-01%201.svg)